I’m going to show you the only eight drawings I ever did in my life and share with you how they transformed my photography.

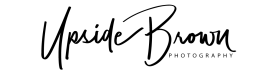

I never took an art class after grade 8 and could barely draw a stick figure. Years later, I found myself teaching physiology to a group of massage students. One day, I was drawing on the whiteboard—maybe it was the chambers of the heart—and I stepped back to look at my sketch, only to think, “What the hell is that?” That’s when I decided to take a leap and enrolled in an art class. I figured starting with an eight-week portrait course, where I could focus on just one head, would be manageable.

The experience was transformative.

I’d always thought drawing, like art in general, was just a right-brain exercise—you put pencil to paper, let it flow, and somehow an image appears. I assumed my brain just wasn’t wired for it. In that first class, we had to draw a skull. I struggled, and my instructor noticed. “Just draw what you see,” he said, then demonstrated by holding his pencil up to measure proportions. “Look at the width compared to the height,” he pointed out. I realized then that I was drawing what I thought a skull should look like, not what was actually in front of me.

It was a revelation. I learned that my mind’s eye had been getting in the way, imposing a sort of “happy face” filter—placing the eyes at the top, the mouth at the bottom, all the features in cartoonish simplicity. But if you look closely, really look, you see that the eyes are positioned toward the middle of the face, not the top. Suddenly, I understood that drawing meant seeing what actually existed, not a mental representation. Sometimes the lines I was copying seemed wrong because my brain was reverting back to what I imagined I was seeing and it couldn’t reconcile the two. But I stuck with drawing lines and shapes as I saw them. By the end of the class, I didn’t just have a blobby mess; I actually had drawn something that looked like a skull.

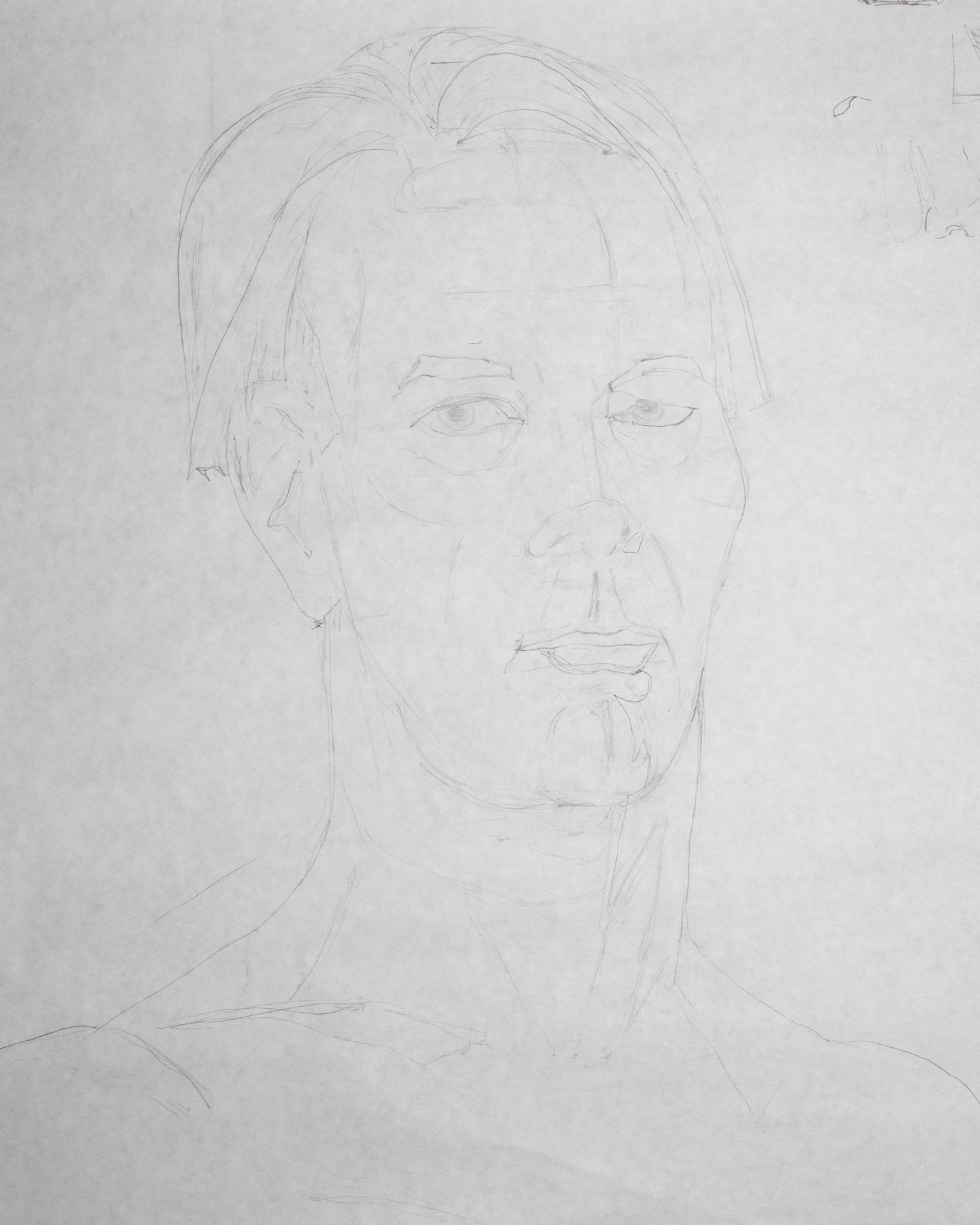

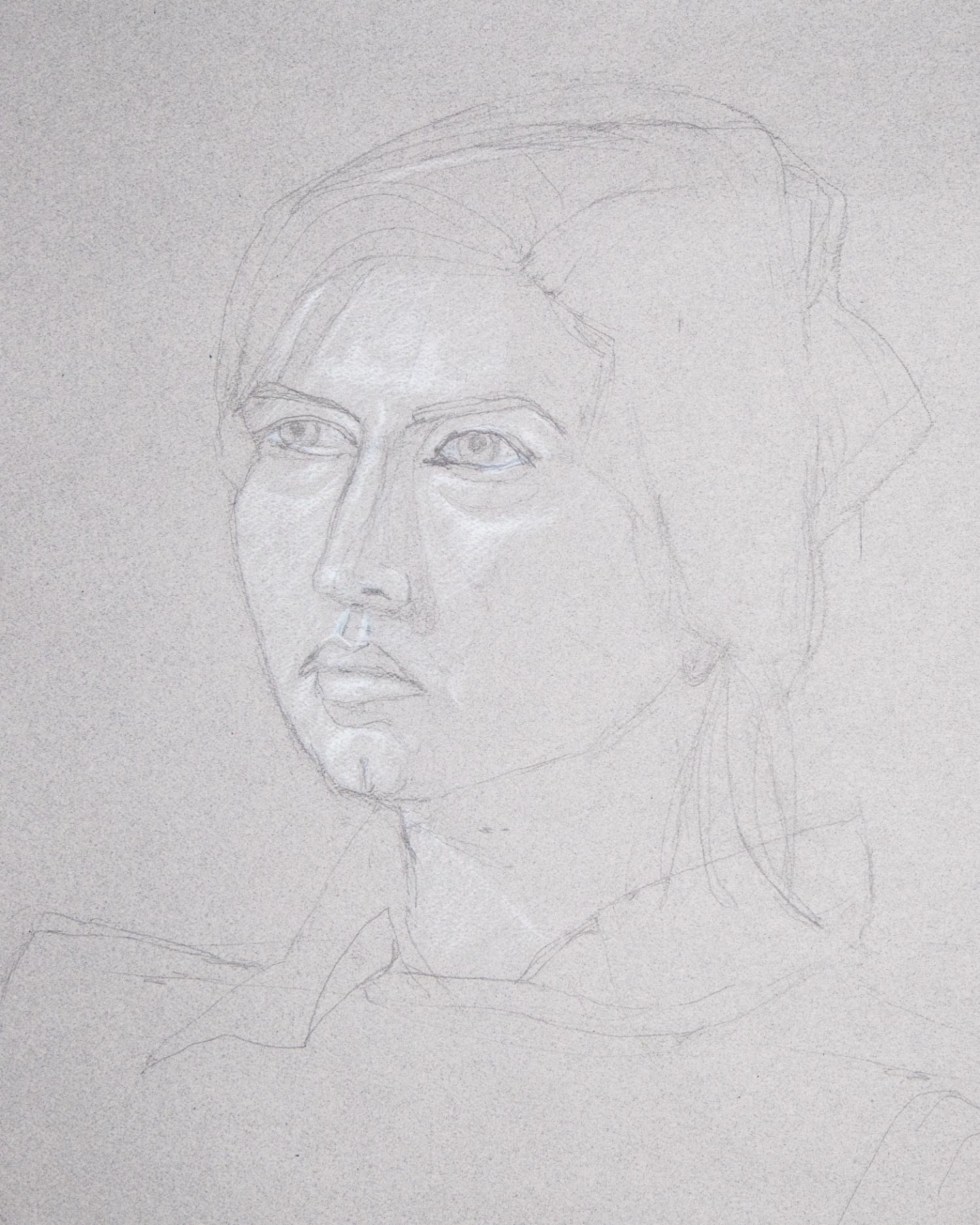

For the next few classes, I focused on drawing only what I saw, carefully noting the proportions. By class four, we were given black paper and a black model. We sketched the figure’s outline and then highlighted areas where the light fell, which brought depth to the image. I’d always assumed shadows defined form, but with darker skin tones, the highlights created the shape. That was a lesson I carried forward into photography. When working with lighter skin, shadows add depth, but with darker skin, highlights create that dimensionality.

In the following classes, I started to see how the face’s highlights followed a pattern: the forehead, tops of the cheeks, bridge of the nose, chin, and bottom lip. These are the same areas I highlight in my portrait editing today to give faces depth. I also started to notice shadows, their gradation, and how they tended to be located in a pattern. As I became more aware of light and shadow and added those elements to my sketch, the images began to become three dimensional. See how these next few sketches look so different from my first three sketches. Instead of looking flat, they pop off the page.

By the final class, it all began to click. My proportions were right, the eyes looked realistic, and the face had dimension. I was blown away. I didn’t know I could draw. But simply by seeing, I was able to draw a true likeness instead of a distorted caricature.

Though I didn’t continue drawing after those eight classes, what I learned became invaluable in my journey as a photographer.

I learned how to truly see.

Looking at faces before that class, I’d never really seen them. My mind created a shortcut—a rough idea of a face, not the real thing. And I had never even noticed the play of light and shadow on anyone’s face. Now, when I photograph, I don’t just snap away. I observe how light interacts with my subject, with skin and fabric, adjusting angles to bring out the most flattering look. It’s something I consciously think about each time I press the shutter.

Being able to actually see isn’t a skill you master in a single shoot. It’s about paying attention to the interplay of light and shadow every time you click. I warn my models ahead of time that if it looks like I’m staring, I’m studying the light’s interaction with them. I ask myself: Do I need to add light to soften shadows, use negative fill to deepen contrast, change the light’s position, or adjust the model’s pose?

Often, I preview my shots in black and white, which helps me see the tonality—the quality and intensity of light and shadow—without color distractions. Color can deceive the eye, making it harder to assess the image’s tonal balance.

If you’re looking to improve your photography, I’d highly recommend an art class. It will train you to see what’s actually in front of you.

This ability to see is a gift, not just for the studio but for life. You see the way light filters through the trees or the shadows cast by objects around you. You notice how someone’s eyes catch and reflect light from nearby surfaces. A whole new sensory world opens up to you.

Even if you never take an art class, you can start developing this skill by truly studying photographs you admire. Find an image that resonates with you and spend five uninterrupted minutes analyzing it. Consider these elements:

- Composition: How are elements arranged in the frame?

- Focus: What’s in focus? How deep is the depth of field?

- Exposure: Which areas are light, and which are dark?

- Form: Does the photo have dimension? How does light shape the subject?

- Color: What palette is used, and what mood does it convey?

- Expression: If it’s a portrait, what does the model’s face and posture communicate?

- Emotion: How does the image make you feel? What’s drawing that response?

Instead of scrolling quickly past images on social media, train yourself to see. It’s a superpower that can transform your photography.